| Elijah Wald – Joseph Shabalala interview |

Back

to the Books

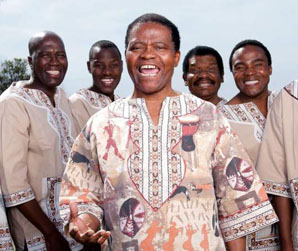

and Other Writing page JOSEPH SHABALALA, interviewed by Elijah Wald, January 1998

The people invite me to talk about that because I grew up on the farm and I know all those cultural things. This is amazing, because I have been invited by the teachers at school. Which means that this [South African] freedom made the people to go back and enjoy good things from the older culture, which is very beautiful, especially for the mothers, fathers, grandmothers. They are very happy to hear that these young ladies they know all the stages before they marry, before they choose how to be in love. They have their time to sit down and talk, and have somebody to lead them, to give them that strength. Therefore people are very happy of that. That was always my aim, because the message I have, I used to say things like counting the warriors in early time, in 1838, and come back to another time, and I used to name those warriors and also talk about if a young man do this and this, even a lady do this and this -- the children used to ask me, "What is the meaning of this, what is this?" Because in my music what is very important is culture. But as the time goes, I forgot about that. I was just composing the songs, I carry on, but now when they remind me that 'You are the one who knows these things because your songs made us go back to the old people to ask "What does this mean?" That's why they invite me to come and encourage the young man, the young ladies. And it is a blessing to me. That was my dream, to send this message to the people. I was encouraging them, "Don't throw away all your things. The good one is good, and the bad one is bad." The music we sing is in the tradition, but the harmony, the melody there, it's my dream. Because before I carry on I feel like somebody's leading me, giving me the rhythm, also the melody and the way to harmonize. The music itself, it's for the people, especially those people who are in rural areas. That's why we said there is a township music, which is for the people who mix it and copy it from the records, from the foreign music. But we have our music on the farm. This type of music now, here in South Africa, you can hear even the trumpet trying to sound like that, because Black Mambazo remind them, don't throw away all your good things. It's good to have your good things, and have some other good things from your friends. The music was for the people on the farm, but the way to develop it, that was an idea which came to me at night, an idea to take the music to the market, because in the dream it was just like somebody was teaching me that you can put this and this, and then you're going to afford to remind the people to market the music, to do many things. But that was not my aim, to market, but my aim was just to put this into the people's mind, just like a preacher who is preaching and reminding people that this is bad, this is good. Now, my people here, they take me as a person who knows everything, who did a good job. Now, this is their time to invite me to come and talk with them, to sit down with them, and the teachers, they brought the young ones together in a way that I was not expecting, that they can afford to do this thing again, these type of what you call stages; the girl must know herself that “My stage is here, and then after this, I'm going to this stage, and then after this I'm going to this stage, and then, now, I'm ready to marry.” The first time when people heard this music, they think they are going to see an old man with a white hair. But when they invite me to Johannesburg, they were surprised. That time was 1972. They said, “This young man, oh, he knows everything! He might be a graduate!” And I said, “Yes, I'm a graduate. Because my mother, my father, my grandmother, they used to tell me about these things from generation to generation.” And they were surprised, from that time up to now. But now, they started to acting, just like they say, “This new South Africa, we must learn something.” The teachers respect me like, “Please come and talk to us,” and I think it's beautiful. Those people who are at the rural areas, they were there doing something. They were professional of that thing. But all along it was just like, “Aw, forget about the old things.” But now, because of these young men, I always praise them, Ladysmith Black Mambazo. I always praise them. Everytime before I start to practice or doing things, I do not forget that I was just like a sick man, and Black Mambazo just like they healed me. Because they loved to listen and they had that patience to sit down after work -- after the whole day they were working 9 to 10 hours -- and listen. They said “Why are you so serious?” And I said, “No, I'm not serious, but I feel like I have something to present our people. I discover that they are all away from their music, and they don't like even themselves, they don't like even their color. I don't know why. They feel like to be a black man is just like I am a Satan.” And I said, “But I think we have something good we can present them.” And the guys were serious after that. I started the group in Ladysmith, but before that I was here in Durban in 1960. In 1958 and '59, I was singing with another group, and then when I came to Durban I sang with another group, Highlanders. In that old time, I remember an old man who came to Durban just to work, and he said to me “Oh, Boy, you’re so serious about these rural things. We have been doing those things years and years, but nobody cares for this. Don't worry about this. You are so young; just go and play the football, do another type of music. Don't be serious.” I just laugh at him. But nowadays, he say “This boy, I know him from his early time when he begin this. He was serious.” I take that name [Black Mambazo] from the span of oxen. In fact, when you have a group, you call them span. “I have my span.” You see, when we were working on the farm, there were three different types of spans: the red one, the colored one, and the black one. And I was the leader of the black span. I'm talking about the plowing, when you cultivate the land. Those span of oxen used to be 16, one span. And the black one was powerful, and I was the leader of that black span. And then, when I started the group, I called them, “This is my black span from Ladysmith.” Ladysmith is the place where we come from, and then black is those span of oxen. And Mambazo is an axe, a chopping axe. The meaning of that is I was hoping that they can have a powerful voice like an axe, to pave the way, to cut all those trees. And also, the time when we were young, from 1950-something to '60, we used to compete with another young ones, and we always warned the competition, and I said “Yes, I have a black axe, just paving the way with their voices.” The changes [in the way we sound] is because of working very hard, it's very difficult to left your family at home for two months, three months, four months. And then the guys, they were getting tired. And then my sons have a chance to join, because even the time when they were at school, when they come back they have another teacher at home. I used to teach them sing and dance. It was very easy for them to take over. They told their mother, “Mother, we want to join father now.” This is very much beautiful, because these young men, they are very active. Now, I used to see myself that the time when I was young I was active like this. Because I'm getting old now. (laughs)

[He says he plans to do “Precious Lord” again, a cappella] The time when I was touring in America, I think it was 1991 I said to my manager can you buy me a video of gospel, because we have a video in the bus. [The video was Say Amen, Somebody, and he was particularly struck by Thomas A. Dorsey.]And as the time goes, I said “Where is this old man?” They said, “He is still alive. And we were in Chicago, doing The Song of Jacob Zulu, a friend brought me to him, but he just died, and I only saw him in his coffin. But I went there, and I was very happy. [Is it easy to blend your style with the American music?] (Loud laughter) Did you talk to the producer about that? It was easy for my sons. Ahh, they were teaching me how to blend with this. To me, I have another way. [Did you know the American songs on this album before?] Not really. You see, to us, we grow up outside, away from the town. I remember the place where I was born, we used to see a white man maybe once a month, maybe twice a month. As the time goes, we used to see a white man once a week, just to come and see and ride the horse and see his cattle there, and go back to town. Because of that, when we left rural areas and come to town we used to sit together, you know that there are hostels, we used to be there, when you visit the township and you come back with a story, “Whew, those people, they're singing another song, we don't know what they're doing!” You see, it was something different. But the time when I came here to Durban, it was a long way from me, from the rural areas to my town, from my town to this big city. And when we came here, I was here in Claremont with my cousin and I used to listen those things, but in my mind the music was stuck there. All the time I used to complain, “This is good, and this one, I don't know, where does this come from?” I grew up in a farm, not even to the places which we used to say, “Oh those people who are believers.” We call them believers. Because even the rural people they know one another that this one is on other side and “Oh, those people are the people who still stick on those same tradition things.” It was just like that. I think that's why the harmony came to me. It was easy to take that harmony because we grew up on the farm. [When I first heard African American music] I was surprised about this. When I came here in Durban my cousin was playing different records, and I said, “These people are trying to imitate us, but they don't know what is this mean.” When I talked to them overseas, I said, “You Black American, the way you sound, you sound like you grew up on the farm. What does this mean to you?” And they told me that this is their feeling, feeling like angry or trying to stop those people who are oppressing them. Because the sound, [he demonstrates a melismatic gospel line], that sound, we use that sound when we drive the span of oxen. But the people who grew up in the township, they don't know that sound from the farm. They heard that song on the record and they are trying to imitate the Black American. But I said, “The Black American, I think they got that into their blood, that at home they sing like this.” It is very interesting, especially to the people here in town. All the township people, they are surprised when I say that. We are coming there [to the US], we are going to sing there and also to stage a play for one and a half months. And we are happy for our South African Airways, they gave us a ticket free. Isn't that wonderful? This is amazing! This is new South Africa now! |

These days I'm working very hard. It's not only touring, singing for people, but also to send the gospel different places and to be invited in many cultural events. Because the music itself encourages the people to be good people. Now they started to doing some function like encouraging the young people, especially the young ladies.

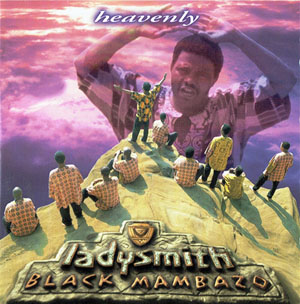

These days I'm working very hard. It's not only touring, singing for people, but also to send the gospel different places and to be invited in many cultural events. Because the music itself encourages the people to be good people. Now they started to doing some function like encouraging the young people, especially the young ladies.  [About his recent album, Heavenly, of African American gospel songs:] I chose the songs. The producer came here, we sit down, we listen all the songs, I say “This one is good, that one is good.” Especially these together with the instruments, I don't want to be so much quotient to that, because I think the person who want me to put the harmony together with that, because, to tell you the truth, I was a guitar player even myself from the beginning, from 1960 up to 1964, but at the time when this music came to me it was something different. If I can take it with the guitar, it means that I can try to suit myself to the guitar. When the harmony came to me at night, it was something like I can build another guitar, to set another type of thing, which can involve in this type of tradition. I enjoy working with other people, because the music, it's for the people, but all the time when I'm doing something, I feel like I need one or two songs without [instruments].

[About his recent album, Heavenly, of African American gospel songs:] I chose the songs. The producer came here, we sit down, we listen all the songs, I say “This one is good, that one is good.” Especially these together with the instruments, I don't want to be so much quotient to that, because I think the person who want me to put the harmony together with that, because, to tell you the truth, I was a guitar player even myself from the beginning, from 1960 up to 1964, but at the time when this music came to me it was something different. If I can take it with the guitar, it means that I can try to suit myself to the guitar. When the harmony came to me at night, it was something like I can build another guitar, to set another type of thing, which can involve in this type of tradition. I enjoy working with other people, because the music, it's for the people, but all the time when I'm doing something, I feel like I need one or two songs without [instruments].